Parks Canada Management Planning: A Guide for Indigenous Leadership

Parks Canada Management Planning: A Guide for Indigenous Leadership by Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Publication Date: January 2023

Introduction

Parks Canada is the country’s largest holder of federal Crown land and manages more than 200 sites, including National Parks, National Park Reserves, National Marine Conservation Areas, National Historic Sites, and one National Urban Park.

More than 300 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities consider the lands and waters found within these federally protected areas as inseparable parts of their culture and homeland. Many Indigenous governments are actively engaging with Parks Canada to negotiate and/or renegotiate the governance and management of these areas in pursuit of asserting their presence on their homelands, practicing their Indigenous rights, and ensuring the stewardship of lands and waters is grounded in Indigenous forms of governance, knowledge, and values.

To support this effort, this Frequently Asked Questions guide clarifies Parks Canada’s collaborative approaches to management planning in recognition of their commitments to reconciliation and adherence to the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), as per the federal government’s 2021 UNDRIP Act.

In their 2018 report, We Rise Together, the Indigenous Circle of Experts outlines several recommendations for the support of Indigenous-led conservation, including the transformation of existing parks and protected areas. Specifically, they called on federal, provincial, and territorial governments to develop collaborative governance and management arrangements for existing parks and protected areas (Recommendation 6.2).

Part of this effort demands a reconsideration of Indigenous-Crown partnerships as supportive approaches to reconciliation in existing protected areas. Agreements between Indigenous governments and Parks Canada have existed for some time. However, they now hold opportunities to shift away from colonial conservation strategies, and towards models and practices rooted in Indigenous knowledge systems, designed in accordance with Indigenous law, and developed through relationships forged in ethical space.

Table of Contents

What is a Parks Canada management plan?

What can Indigenous governments achieve from management planning with Parks Canada?

What does the Parks Canada management planning process look like?

What are the stages of the management planning cycle?

Who is involved in Parks Canada’s management planning process?

How does cooperative management influence Parks Canada’s management planning process?

Examples of Indigenous collaboration in Parks Canada’s management planning process

An illustration of three women standing at a table filleting fish. (Illustration by Nicole Burton).

How to use this guide

The purpose of this guide is to inform and support Indigenous governments as they engage with Parks Canada’s management planning process in its current form. While there are several types of agreements Indigenous governments can establish with Parks Canada, this guide focuses on management planning.

Each protected area managed under Parks Canada goes through a management planning process with Indigenous input. This is required by legislation and is best practice. This guide provides Indigenous governments with clear definitions of key terms and an assessment of what is possible through their collaboration in Parks Canada’s management planning process.

It should be noted that this guide reflects Parks Canada’s management planning process as of the time of this publication and that this process may change according to Canada’s political cycle. Note that current policy development at Parks Canada is directed at renewing support and providing alternative approaches for elevating Indigenous leadership in protected area management, such as the Indigenous Stewardship Framework.

Key definitions and examples of Indigenous collaboration in management planning are found at the end of the guide.

This guide was developed by Kai Bruce (Concordia University) in collaboration with the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership (CRP), an Indigenous-led network that brings together a diverse range of partners to advance Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) across Canada and transform conservation strategy and practice by centring Indigenous leadership, rights, responsibilities, and knowledge. The guide was created in a collaborative spirit with generous input from Peter Lariviere, Graham Dodds, Karen Haugen, and Emily Martin.

Key Takeaways

- Indigenous governments can engage in park management planning as a way of asserting their vision for how a park can be managed and to determine if future agreements need to be developed.

- There is a strong rationale (e.g. legal requirements, reconciliation commitments, etc.) for Indigenous governments and Parks Canada to collaboratively engage in management planning. Should Indigenous governments feel as though their input into management planning is not being adequately addressed, they can seek ways of increasing cooperative engagement.

- Formalized cooperative management agreements or structures to facilitate a collaborative management planning approach may or may not exist. Similar outcomes may be achieved through either arrangement.

How is Parks Canada’s management planning process important to Indigenous governments and communities?

Management planning is one of many entry points for Indigenous governments to assert their presence and affect change in the management and stewardship of National Parks, National Marine Conservation Areas, and National Historic Sites that overlap with their territories and homelands.

Management planning is a mechanism for Indigenous governments to negotiate based on their interests. Parks Canada has committed to developing nation-to-nation relationships in the spirit of reconciliation. In addition, recent projects have demonstrated Parks Canada’s willingness in managing parks in accordance with Indigenous worldviews, knowledge systems, and forms of governance (e.g. Thaidene Nëné Agreements, Ndahecho Gondié Gháádé Agreement for Nahanni National Park Reserve). Management planning can be a platform for Indigenous governments to build relationships and recommend new cooperative management approaches.

Parks Canada has a legal requirement to consult with Indigenous groups during the management planning process. Furthermore, management planning is one of the few legislated processes that guide Parks Canada’s management practices. Therefore, management planning offers opportunities to reconcile the co-existence of Indigenous homelands and Parks Canada heritage places and to guide management objectives toward Indigenous priorities and aspirations.

What is a Parks Canada management plan?

A Parks Canada management plan is the final product of Parks Canada’s management planning process. The management plan is the central guiding document for future park management. It is a results-based document that focuses on the desired vision for a protected area’s 10-year planning horizon.

Each plan is structured around this vision and a broad set of key strategies which allows for openness and flexibility in deciding what actions need to be taken and how they will be carried out. Following changes to Parks Canada’s management planning and reporting policies in 2013, management plans are primarily strategic documents and no longer include a detailed work plan.

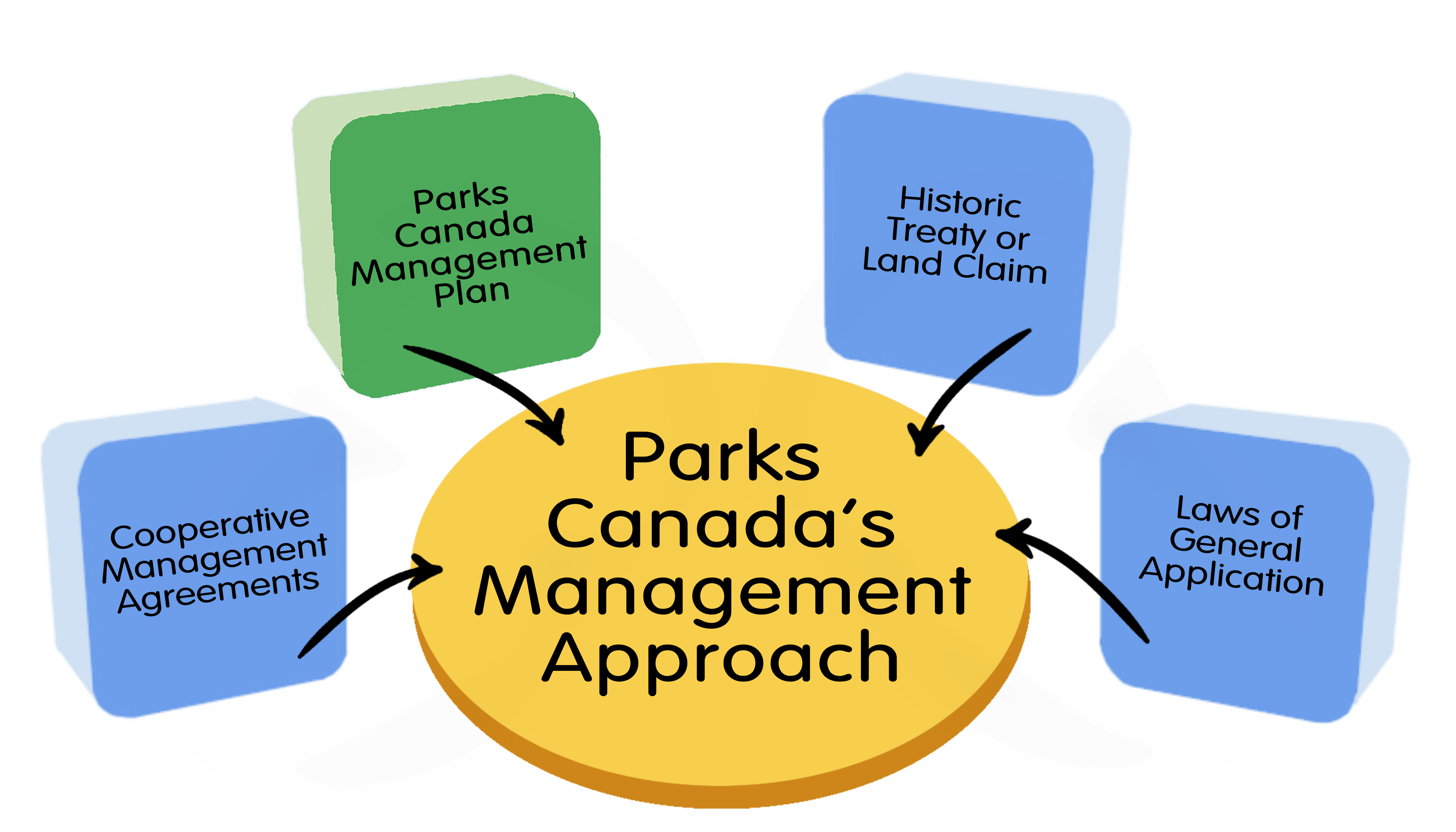

Figure 1: Parks Canada manages its protected areas in accordance with a management plan, cooperative management agreements, historical and modern treaty obligations, and relevant federal, provincial, and territorial laws. (Diagram by Nicole Burton).

The creation of a management plan is one of the few legislated processes connected to protected area management. It is approved by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change and is tabled in Parliament. As such it is a foundational document with opportunities to advance Indigenous involvement in environmental stewardship and to reconcile the co-existence of Indigenous homelands and existing protected areas.

What can Indigenous governments achieve from management planning with Parks Canada?

- Through collaboration in the management planning process, Indigenous governments and Parks Canada can establish a shared conceptual vision for the long-term desired state of the protected area.

- The management plan sets out key strategies, objectives, and targets for management that work toward that shared vision. Indigenous involvement and cooperative management approaches may be a key strategy itself or built into others. Management planning is a place to establish a mutual commitment to advance shared governance approaches, which may lead to the negotiation of a formal agreement (e.g., cooperative management agreement, harvest agreement).

- Other key topics may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Governance approaches and objectives (e.g., cooperative management approaches).

- Protection and management of natural and cultural resources.

- Approaches to recognize and introduce Indigenous conservation practices such as traditional harvest.

- Respectful use of Indigenous knowledge(s), language, and how Indigenous cultures are presented in park informational and educational materials.

- Park zoning, which, for example, can identify ecologically or culturally sensitive features and sites for special protection.

- Indigenous cultural programming and land-based projects.

- Tourism, employment, and training objectives.

- While Indigenous governments are to be consulted throughout the entire management planning process, Parks Canada also engages public citizens along with other stakeholders during the plan’s preparation stage. Parks Canada is therefore accountable to Indigenous partners and the broader public, and parks are managed on their collective behalf.

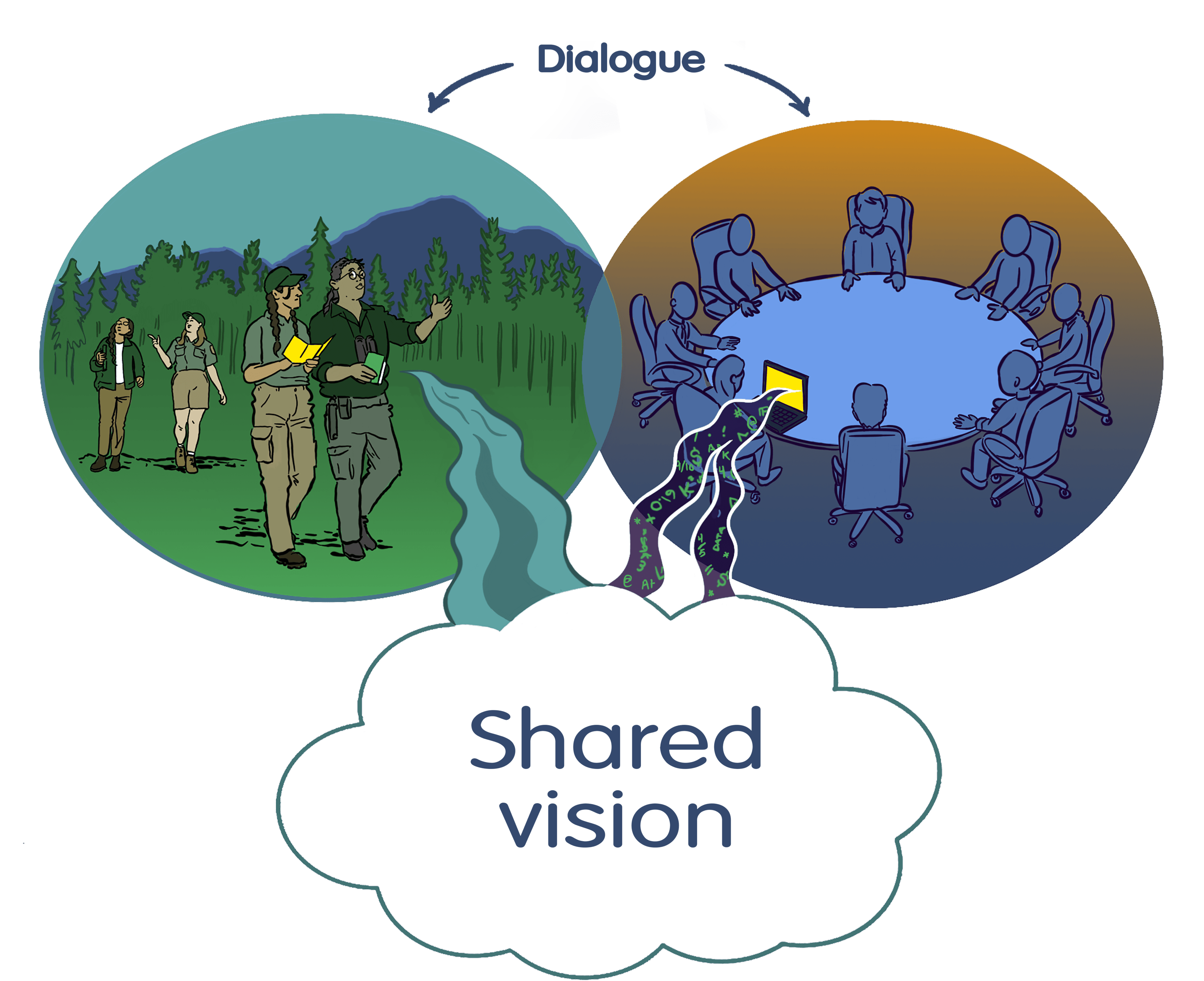

Figure 2: Respect for different worldviews and knowledge systems can help build a shared vision for the future of the protected area. The shared vision should reflect both Indigenous and Parks Canada objectives. (Diagram by Nicole Burton).

What does the Parks Canada management planning process look like?

- The Parks Canada management planning process takes place over a 10-year cycle.

- The plan takes roughly two years to develop, but timelines will vary from site to site.

- The management planning cycle follows several stages (see Management Planning Cycle flow chart below).

- Indigenous partners can self-advocate and determine their engagement levels at any stage.

- Indigenous engagement is different and separate from public consultation processes.

- Parks Canada may fund and/or provide third-party facilitators to support collaboration in the planning process.

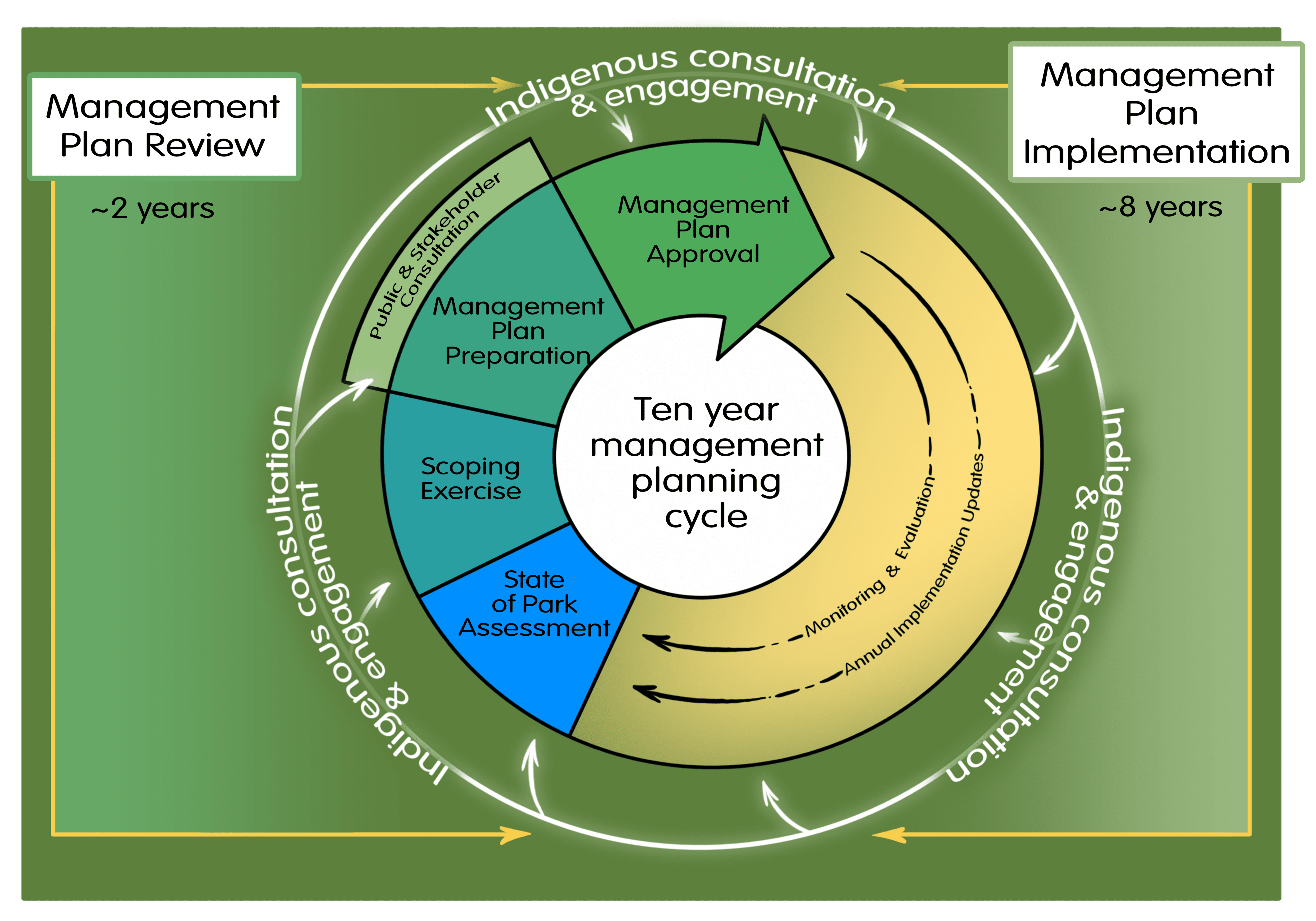

Figure 3: This diagram outlines Parks Canada’s 10-year management planning cycle. The planning cycle is broken into two parts: management plan review (~2 years) and management plan implementation (~8 years). The stages of the review process include the state of the park assessment, the scoping exercise, management plan preparation, and management plan approval.

Management plan implementation includes ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the plan itself which includes annual implementation reporting to Indigenous partners and the public. Indigenous partners can decide their level of engagement at any stage in the management planning cycle. (Diagram by Nicole Burton).

What are the stages of the management planning cycle?

The following section explains the stages seen in the management planning cycle in detail.

- Most importantly, Indigenous engagement and consultation is an ongoing process. Indigenous partners can decide their level of engagement at any stage (as shown in the flow chart). Multiple Indigenous governments may be involved in one management planning process for the same protected area. Each group may have a different level of engagement depending on their interests and objectives. This may increase the time, funding, and resources needed for appropriate Indigenous involvement.

- The State of the Park Assessment (SOPA) is a standalone document that reports the current condition of a heritage place and assesses its performance in meeting the established objectives of Parks Canada’s mandate. This assessment applies to national parks and other heritage sites such as National Marine Conservation Areas (NMCAs). This report is developed every ten years during the planning cycle. The SOPA is based on a national suite of indicators, including Indigenous Relations, which is assessed through methods such as direct engagement with Indigenous partners or statistical reports (e.g., employment data). Indigenous partners can collaborate with Parks Canada management to assess ecological indicators by sharing their Indigenous Knowledge. The SOPA will help to identify strategies and objectives through the Scoping Document Exercise, explained below.

- The Scoping Document Exercise sets out the terms and conditions of the management planning process. This document can be developed collaboratively and includes the identification and timing of the tasks and responsibilities of each party. The Scoping Document and the SOPA are key inputs for the development of the management plan. The Scoping Document is recommended by the Indigenous government (as desired) and the Superintendent to the Senior Vice President Operations of Parks Canada for approval.

- The Preparation Stage of the management plan involves drafting and further dialogue. This may be an important stage for Indigenous engagement and consultation that may involve various working groups, including Indigenous leadership, Elders, youth, women, active hunters, and/or other community members. Public Consultation, which occurs separately from any Indigenous engagement, will take place during the preparation stage.

- In the Approval Stage, the final management plan is recommended by Indigenous government(s) (as desired), the Superintendent, and the CEO to the Minister to be tabled for approval. Parks Canada recognizes that for a management plan to work, it needs everyone’s support. In some cases, the management plan will not be published without support at the Indigenous leadership level. Additional signatories (e.g., park advisory body, cooperative management board) may be added to the recommendation page or may express their support for the plan through a separate letter of support. Partners may still introduce Indigenous-led programming and cooperative management approaches in absence of a management plan (refer to the Clam Garden Restoration Project in Gulf Islands National Park Reserve).

- Management Plan Implementation may involve continued engagement with Indigenous partners as set out in the management plan, or as agreed upon through separate agreements or commitments. Further, Indigenous partners can take part in developing reports, such as Annual Progress Reports or Indigenous Newsletters, that communicate the progress of management implementation to Indigenous groups, stakeholders, and the public.

Who is involved in Parks Canada’s management planning process?

As it currently stands, Parks Canada’s Strategic Policy and Planning Directorate assigns senior planners to individual parks and other sites to develop management plans. While a federal Minister provides approval for the final management plan on the Canadian government’s behalf, the Field Unit Superintendent (FUS) is accountable for ensuring all aspects of management planning and implementation are carried out properly.

The FUS is responsible for guiding the relationships with Indigenous governments to facilitate engagement and consultation throughout management planning review and implementation. Depending on the context, multiple Indigenous governments may be involved in management planning in various capacities. Indigenous Liaison Officers and/or planners hired by Indigenous partners may play a large role in facilitating communication between partners during these phases. Working groups, that can include Elders, women, youth, active hunters, and other community members, may be established to inform management plan review and implementation.

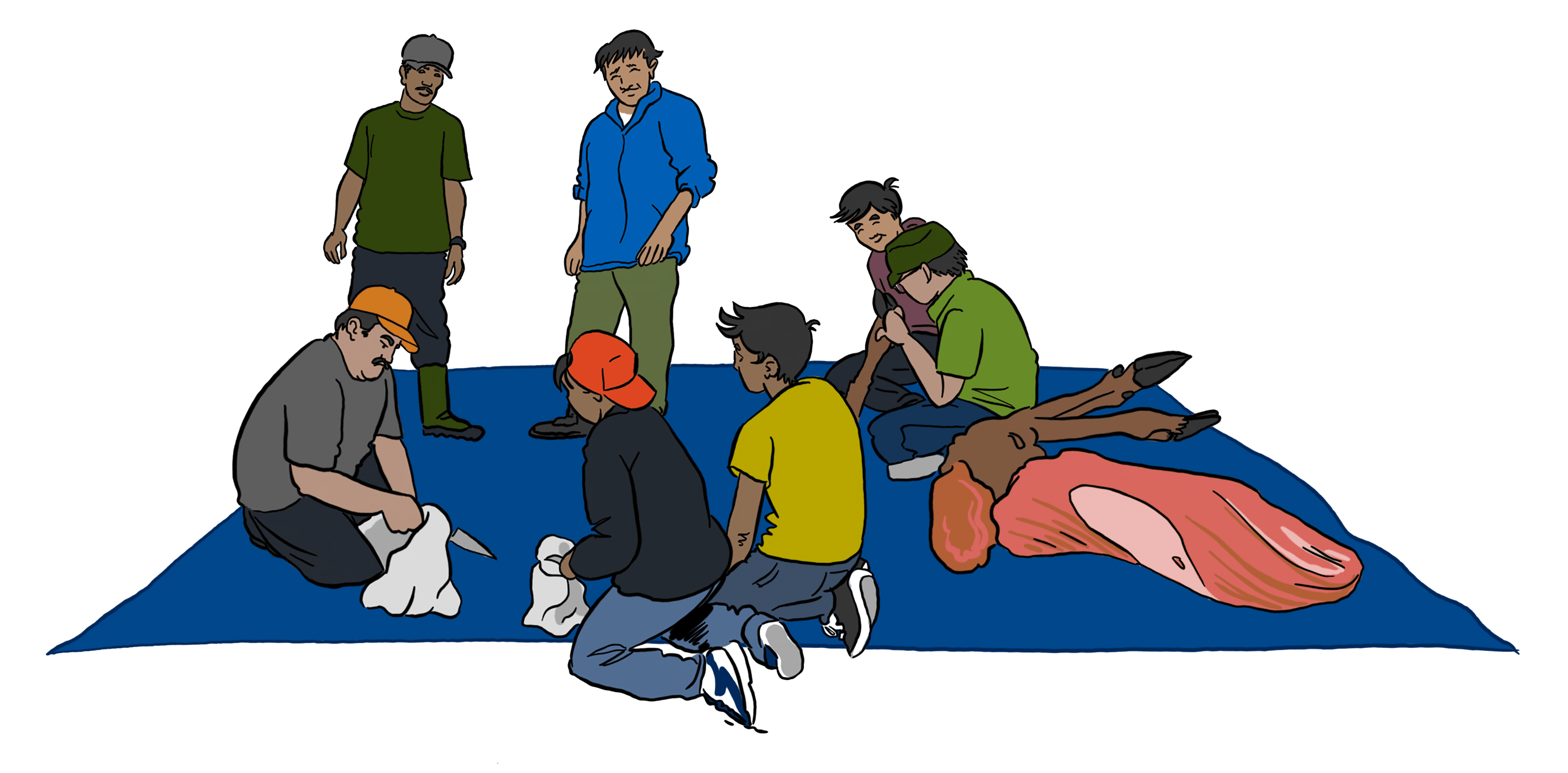

An illustration of a group of men and boys gathered around a blue tarp where a moose is being harvested. (Illustration by Nicole Burton).

How does cooperative management influence Parks Canada’s management planning process?

Cooperative agreements are foundational to a shared decision-making framework and can cement roles, responsibilities, and expectations in management planning as well as other areas of management and stewardship. Time, resources, and capacity are key factors for building a collaborative management approach. However, successful collaborative management relies equally on relationships and a mutual commitment to working together on the ground.

When in place, cooperative management agreements help to guide the management planning process by setting the foundation for positive working relationships. In addition, Parks Canada is legally obligated to manage a Park in accordance with these agreements, along with the management plan, historical and modern treaty obligations, and other Canadian laws.

Under many of these agreements, cooperative management structures advise the Minister on aspects of heritage place planning and operation, and on the means to achieve the purposes set out in plans and agreements.

Not all agreements under Parks Canada share the same level of legal authority. The influence of a cooperative agreement on planning and management may therefore vary depending on the type of agreement.

Cooperative management agreements range from informal interest-based agreements (e.g., Memorandum of Understanding, Terms of Reference) to formal arrangements that are detailed in constitutionally protected agreements (e.g., park establishment agreements, land claims).

In northern national parks (e.g., Qausuittuq National Park, Torngat Mountains National Park Reserve), cooperative planning is often mandated through land claims-based park establishment agreements, modern treaties, or Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreements (IIBAs). These constitutionally protected agreements lay out cooperative planning approaches (i.e., principles) and structures (e.g., boards, committees).

In less formal settings (e.g., Riding Mountain National Park, Gulf Islands National Park Reserve), cooperative planning approaches, including committees (e.g., Advisory Circles or Forums), are done ad hoc (as needed) or established through a Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) or similar agreement.

In other words, collaborative planning can take place in legally-mandated settings and less formal settings. Where no cooperative management agreements exist, a cooperative approach to management planning with Indigenous Peoples may still be pursued and achieve similar outcomes to parks managed under a cooperative management agreement. This is because Parks Canada consults with Indigenous Peoples as a best practice and under its legal requirement to consult with Indigenous partners during management planning.

In addition, if the Government of Canada’s duty to consult is triggered through conduct that may impact Aboriginal and/or treaty rights, a cooperative approach to management planning is required.

Clarification of key terms

Parks Canada’s management terminology at times mirrors those of Indigenous governments. Parks Canada uses a management plan to establish a vision for the future management of its protected areas, whereas an Indigenous government may develop a Strategic Plan to establish a vision for its traditional territory and homeland.

- Shared Governance vs Cooperative Management vs Co-management

Parks Canada uses shared governance as an umbrella term to encompass the spectrum of cooperative arrangements within their system. According to Parks Canada, “the term cooperative management is used to describe different models that involve Indigenous peoples in the planning and management of national parks without limiting the authority of the Minister under the Canada National Parks Act (2000)”. Co-management, cooperative management, and joint management have been used interchangeably over time and vary between protected areas. These terms do not represent distinct management practices. The important term is the one that is mutually adopted by all parties.

- Engagement vs Consultation There is a legal requirement to consult during management planning according to the Canadian National Parks Act. Canada’s duty to consult may also be triggered during management planning depending on the topics being discussed. Consultation, in either case, is characterized by similar principles of good faith, providing full information in a timely manner, engaging in two-way dialogue on topics of interest, and accommodation for the individual process needs of all parties within reason. Engagement is an umbrella term for working with others, from providing basic information to fulsome cooperative management approaches.

Examples of Indigenous collaboration in Parks Canada’s management planning process

The following examples highlight Indigenous collaboration in Parks Canada management planning. Legal and political context plays a large role in outcomes. Examples focus on southern national parks and less formalized cooperative planning settings.

An illustration of two people kneeling to harvest berries from a bush. (Illustration by Nicole Burton).

Indigenous communities all share different histories with Parks Canada. Note that examples from protected areas where multiple Indigenous governments are involved may not be readily applied to bilateral contexts. Click on the links to learn more.

All current drafted and finalized Parks Canada management plans can be accessed at the Parks Canada Library site at this link: https://parks.canada.ca/agence-agency/bib-lib/plans/docs2bi

The following resources include management plans with key strategies for moving towards shared governance/cooperative management agreements:

- 2022 Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Park Management Plan (Ktunaxa Nation Council, the Syilx/Okanagan Nation, and five Secwépemc bands: Adams Lake, Little Shuswap Lake, Neskonlith, Shuswap, and Splatsin)

- 2015 Pukaskwa National Park Management Plan (various Anishinaabeg First Nations and Métis Nations, Robinson-Huron Treaty Group)

- 2010 and 2020 Draft Point Pelee National Park Management Plans (Caldwell First Nation and Walpole Island First Nation)

- 2007 Riding Mountain National Park Management Plan (Coalition of First Nations with Interests in Riding Mountain National Park)

- 2014 Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve Management Plan (Nutashkuan and Ekuanitshit First Nations) (Plan available in Innu-aimun)

- 2021 Kouchibouguac National Park Management Plan (Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn Inc. (MTI) group, representing eight Mi’gmaq communities in New Brunswick, and the community of Elsipogtog, represented by the Kopit Lodge organization)

Management plans where zoning has been used to protect culturally important

sites/resources:

- 2022 Waterton Lakes National Park Management Plan (Siksikaitsitapi or Blackfoot Confederacy)

Management plans with objectives to recognize and allow for Indigenous conservation (e.g., traditional harvesting)

- Jasper National Park (Jasper Indigenous Forum representing various Indigenous

governments)

- Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Park

Management plans where key visions are structured in Indigenous worldviews:

- 2022 Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site Management Plan (Mikma’q of Nova Scotia) (a publicly available management plan is forthcoming.)

- 2018 Gwaii Haanas Gina ’Waadluxan KilGuhlGa Land-Sea-People Management Plan (Haida Nation)

Management plans where Indigenous partners have engaged in plan preparation:

- Kootenay National Park of Canada

- Waterton Lakes National Park

- 2022 Waterton Lakes National Park Management Plan

- Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Park

- Jasper National Park (Jasper Indigenous Forum representing several Indigenous groups)

Management plans published in Indigenous languages:

Management plans where Indigenous partners are formally recognized in plan recommendation:

- Batoche National Historic Site (Métis Nation – Saskatchewan)

- Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve (Haida Nation)

Example of an Annual Implementation Report:

Example of Indigenous Newsletter

Examples where Indigenous-led and collaborative programming has occurred in absence of a management plan or other agreement:

- Sea Garden Restoration: Gulf Islands National Park Reserve (W̱SÁNEĆ, Tseycum First Nation, Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group)

- W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council

Additional resources from Parks Canada: