Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks

Authors

Story of Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Publication Date: June 2022

Visual Journey through Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks

Glossary of Nuu-chah-nulth terms

C’is-a-qis

Heelboom Bay on Meares Island

Ha’houlthii

Traditional territories of the Tla-o-qui-aht ha’wiih

Ha’uukmin

Feast bowl (Tla-o-qui-aht name for Kennedy Lake)

Ha’wiih

Hereditary leaders of the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation with particular inherited rights, responsibilities and relationships in the ha’houlthii

ha’wilthmis

Rights and responsibilities of the ha’wiih

hishuk-ish tsawalk

The Nuu-chah-nulth articulation of the principle that everything is one and everything is connected

Iisaak

Respect (to observe, appreciate, and act accordingly)

qwa siin hap

Leave as it is: a land designation in Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks that refers to rare and sensitive old-growth forest ecosystems and cultural refuges

uuya thluk nish

We take care of: a land designation in Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks that refers to areas needing ecological restoration

uuya thluk nish, uuya thluk usmaa

The Nuu-chah-nulth principle admonishing us to take care of ourselves, and to take care of our precious ones

Wanachus-Hilthuu’is

The two mountains that comprise Meares Island

About Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks

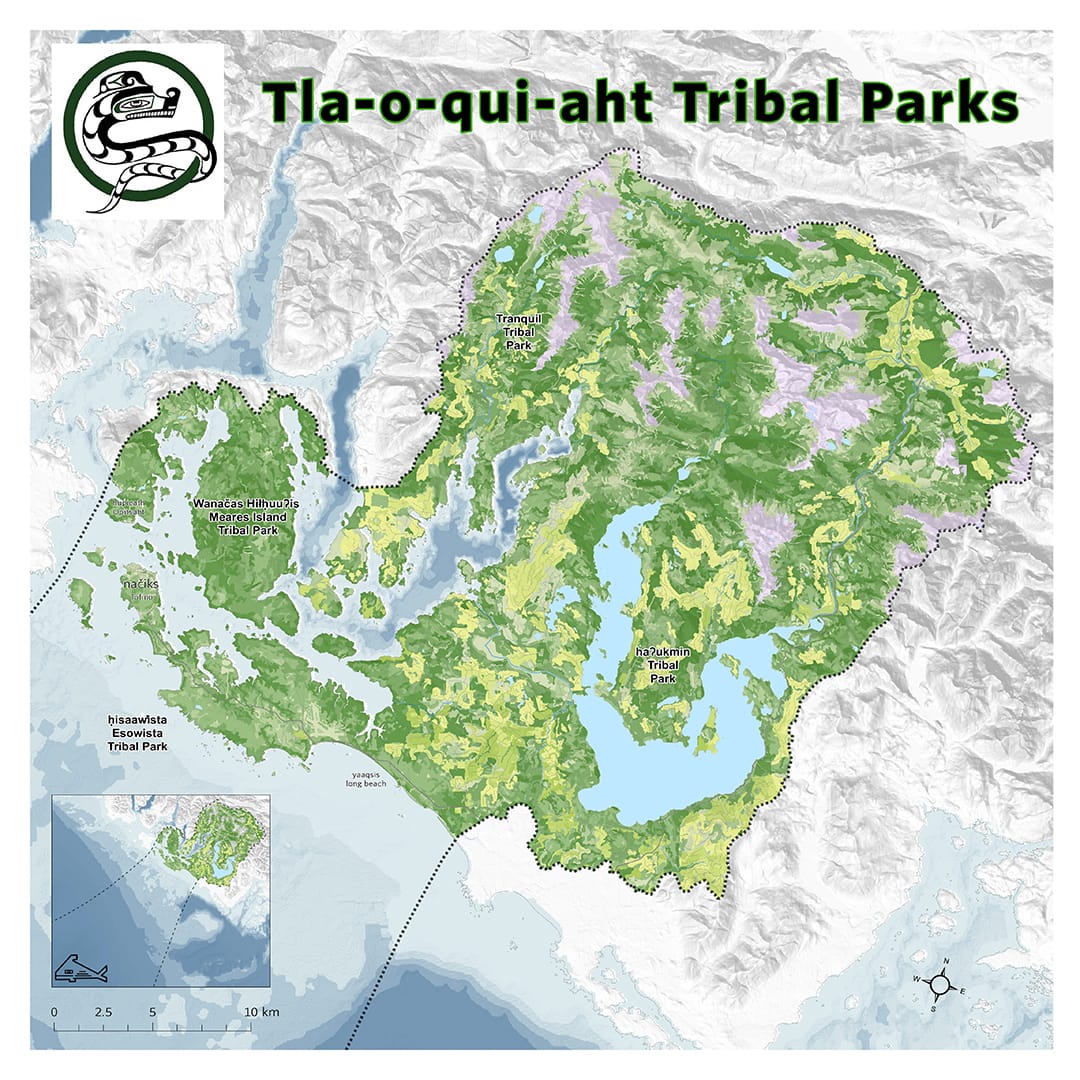

In Tla-o-qui-aht Territory, the Nuu-chah-nulth teachings of iisaak have been in place for millennia to enrich life and support biodiversity for future generations. In 1984, the Tla-o-qui-aht Peoples declared the Meares Island (Wanachus-Hilthuu’is) Tribal Park as a practice of iisaak to protect the territory from rampant clearcut logging. The Nation’s entire territory is now included in four Tribal Parks. which are implementing Indigenous Watershed Governance methodologies to promote environmental security and sustainable livelihoods. In Clayoquot Sound on the West Coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation has conceived an Indigenous Watershed Governance methodology to promote environmental security and sustainable livelihoods: Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. Tribal Parks have become a key strategy of the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation in their ongoing struggle to uphold traditional rights and responsibilities in their traditional territories.

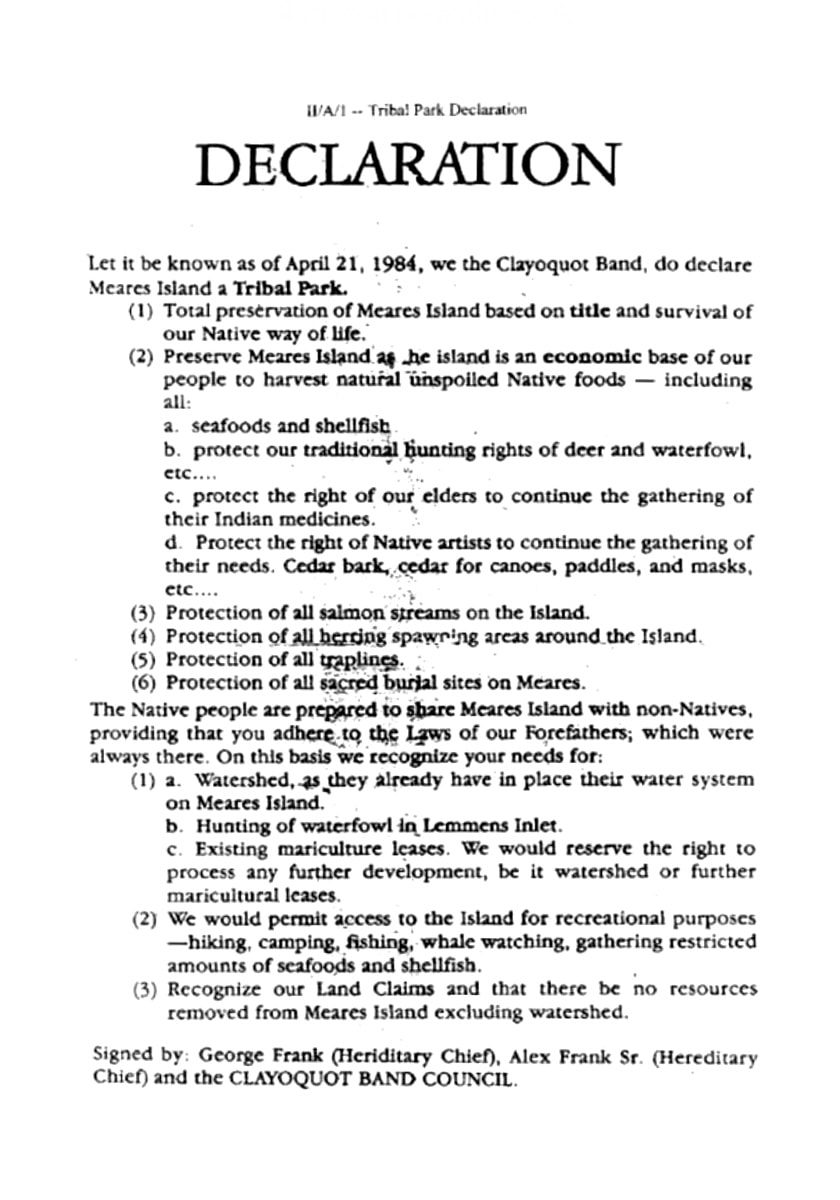

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks were originally articulated in the midst of the struggle against unchecked clearcut logging of old-growth primary rainforests in unceded Tla-o-qui-aht territories. In 1984, the Tla-o-qui-aht leadership issued the Meares Island (Wanachus-Hilthuu’is) Tribal Park Declaration. The declaration was combined with a direct-action strategy, as Tla-o-qui-aht members and their Allies maintained a peaceful blockade to prevent the loggers from bringing their equipment ashore. In addition, the Tla-o-qui-aht launched legal proceedings, ultimately successful, which resulted in a court injunction preventing logging of Meares Island until Indigenous rights and title are resolved. The old-growth forests of Meares Island remain standing to this day. Since 1984, the Tla-o-qui-aht have established three additional Tribal Parks: Ha’uukmin (Kennedy Lake Watershed), Tranquil Tribal Park and Esowista Tribal Park.

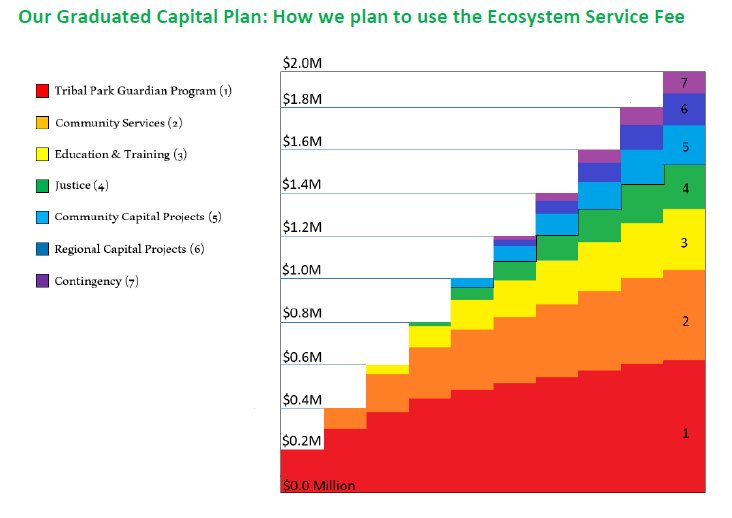

Collectively, the four Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks encompass all of Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation territory. The Tribal Parks are a prime example of Indigenous leadership in conservation in Canada. They include 500-year plans for stewardship, ecological restoration, and community economic development. Tla–o-qui-aht Tribal Parks have pioneered an Ecosystem Stewardship Contribution program entitled “Tribal Parks Allies,” which partners with local businesses to fund Tribal Parks Guardians and ecological restoration initiatives. The Tribal Parks also include community economic development solutions such as ecotourism, minimal impact run-of-river hydroelectric projects, and Indigenous housing solutions.

This video describes the motivation for the creation of the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. Produced by IISAAK OLAM Foundation, 2021.

Ha’huulthii (Traditional Territories)

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks are located in the Ha’huulthii (traditional territories) of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, one of the Nuu-chah-nulth-speaking nations on the West Coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia. The four Tribal Parks encompass all of Tla-o-qui-aht territory, which in turn is defined by natural watershed areas, extending from Sutton Pass along Highway 4 to fishing sites beyond the horizon of the Pacific Ocean. Esowista Tribal Park overlaps with Long Beach in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. Surrounding and including the town of Tofino, Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks are the gateway to the famous Clayoquot Sound, which includes the largest area of intact old growth redcedar-hemlock rainforest remaining on Vancouver Island. In 2000, Clayoquot Sound was designated a United Nations Biosphere Region.

Collectively, Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks include the land and its deep subsurface area, the water and open ocean going offshore at least 100 kilometres, and the airspace above into the earth’s atmosphere. The Tribal Parks encompass shorelines, lowlands, and mountains on Vancouver Island and numerous islands and islets in Clayoquot Sound and facing the open Pacific Ocean. Inland water bodies include Ha’uukmin (Kennedy Lake) and Tofino Inlet. Esowista Tribal Park faces the open Pacific Ocean and extends to off shore Tla-o-qui-aht fishing sites.

Timeline for Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks

Note: Tla-o-qui-aht history does NOT begin with colonization. This timeline merely chronicles the history since colonial Canadian disruption.

Governance and Decision-Making

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks are an example of sole Indigenous governance of IPCAs (ICE Report, pg. 45). Federal and provincial governments have never formally recognized the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks, and indeed the Tribal Parks have not sought official designation as a provincial or federal protected area under existing legislation. However, Tribal Parks represent an assertion of Indigenous governance, which is protected through Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution. Renowned Indigenous rights lawyer Jack Woodward has suggested that Tribal Parks can thus be considered “constitutional parks.”1 They represent a “projection of sovereignty [and responsibility] over contested terrain.”2

This video produced by the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership and the IISAAK OLAM Foundation explored Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks from its origins in 1984 to present-day governance, key partnerships, and a unique financial model, this webinar will provide attendees with lessons and tools that gave this IPCA life and momentum.

Role of Indigenous Law

All of the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks have been established under Tla-o-qui-aht laws. In fact, Meares Island Tribal Park was established in direct response to the violation of these laws. British Columbia’s granting of industrial tree farm licenses without Tla-o-qui-aht consent and without a treaty constituted a violation of both natural law and Nuu-chah-nulth law. These licenses also violated Canadian constitutional law by disregarding the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which is a foundational constitutional document in Canada (Eli Enns, webinar Nov 4, 2020).

Tribal Parks are the current articulation of what Tla-o-qui-aht ancestors have always done in exercising their responsibilities to the Ha’houlthii. These ecological roles and responsibilities have been upheld for millennia. Ha’houlthii refers not just to a territory but the relationship with the living spirit of place; it is like an intergenerational marriage with a living being (Gisele Martin, webinar Nov 4, 2020).

These are the sorts of relationships and responsibilities that Tribal Parks are working to strengthen and revitalize. In doing so, Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks are managing for “abundability” rather than the industrial goal of “sustainability” [i.e., sustained yield] (Joe Martin, webinar Nov 4, 2020).

In Tla-o-qui-aht society, a high value is placed on personal responsibility. The highest law of the Nuu-chah-nulth constitution, iisaak, means respect, or to “observe, appreciate, and act accordingly.” The law of iisaak was a core motivating and guiding principle for the Meares Island Tribal Park Declaration in 1984. Iisaak, together with other laws represented in the Tla-o-qui-aht crests and totem poles, guides decision-making in the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. The Sea Serpent crest, which is the emblem of Tribal Parks, represents the connection between observation and action, listening not only with our heads but our hearts. Decisions in Tribal Parks are informed by a deep knowledge and connection with the territory at a personal level (Gisele Martin, webinar Nov 4, 2020).

The crests and totem poles constitute the Nuu-chah-nulth constitution. The stories connected to these crests are told from one generation to the next provide a roadmap for Tribal Parks decision making and governance. This is not a manual of rules and procedures that one might find in a document. Rather, the stories become internalized as part of one’s “operating system,” which then informs action. These laws can be summarized in principles such as uiuthluk nish, uiuthluk usmaa: to take care of ourselves, and to take care of our precious ones (Eli Enns, webinar Nov 4, 2020).

The Ha’wiih, or hereditary chiefs, are the traditional caretakers of the Tla-o-qui-aht Ha’houlthii. As the Ha’uukmin Tribal Park Management Plan explains,

Tla-o-qui-aht governance is integrated into our culture and society and its laws are based on respect and ensuring the well being of our people and the environment. The Hereditary Chiefs are known collectively as Ha’wiih, and each Ha’wiih has complete title and rights within their Ha’huulthii. Ha’huulthii translates as all within their traditional territory and includes certain responsibilities to rivers, food, medicines, songs, dances and ceremonies. Each of these items is passed down to the Ha’wiih through inherent rights or marriage. The Ha’wiih have a responsibility to the Creator to take care of all within the Ha’huulthii.

Land Relationship Planning and Zoning processes

The Tribal Parks include 500-year plans for stewardship, ecological restoration, and community economic development. For example, a land management plan was developed for the Ha’uukmin Tribal Park through an extensive series of consultations and workshops that engaged Tla-o-qui-aht Elders and community members, neighbouring First Nations, other local communities, governments, environmental groups, industry, and technical experts. The plan subdivides Ha’uukmin Tribal Park into two management zones. Rare and valuable old-growth ecosystems and cultural refuges are designated as qwa siin hap, which means “leave as it is” and are off-limits to all development. Other areas are zoned as uuya thluk nish, which means “we take care of.” These areas include ecological restoration activities, low-impact forestry, a fish hatchery, salmon habitat restoration areas, low-impact hydroelectric installations, and ecotourism operations. Environmentally destructive activities such as industrial mining or clear-cut logging are prohibited throughout the four Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks.

Partnerships and Relationships

Partnerships have played and continue to play an important role in the development and evolution of Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. A diverse coalition of Allies enabled the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation to assert and defend the Tribal Parks against unwanted development in the 1980s and ‘90s, and today both those legacy Allies and a new cohort of Allies are supporting our vision. The Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks Allies Certification Standard sets baseline criteria for “right relationship” between Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and Allies while providing opportunities for settlers to connect to Tla-o-qui-aht cultural teachings about how to live well in relationship with the network of life that comprises the Tla-o-qui-aht Ha’huulthi.

Conservation Alliances

Non-Indigenous environmentalists and conservation organizations joined with the Tla-o-qui-aht to oppose clear-cut logging of the old-growth rainforest, playing an especially important role in the large-scale protests and global consumer boycotts against old-growth logging in the 1990s. Today, seven conservation organizations comprise the Clayoquot Sound Conservation Alliance: the Wilderness Committee, Stand.earth, Friends of Clayoquot Sound, Greenpeace, Sierra Club, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Canopy.

There have also been challenges in the relationship between Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks and conservation interests. For years, conservationists have treated Clayoquot Sound as a pristine wilderness – only more recently have these organizations begun to acknowledge the deep human history and interconnectedness of the land and Tla-o-qui-aht communities. Conservation organizations continue to promote the development of a conservation economy in Clayoquot Sound while supporting First Nations’ efforts to prevent logging in all remaining intact rainforest valleys and islands.

Academic Collaborations

Academic collaborations have also played a role in raising the profile of Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. In 2007, Ha’uukmin Tribal Park became part of a multi-sited research project on protected areas and poverty reduction based at Vancouver Island University (then Malaspina University College). This project linked Tribal Parks with the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, thereby building wider credibility and recognition of the Tribal Parks model for conservation. Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks have been featured in at least three academic articles, as well as the Gleb Raygorodetsky’s book Archipelago of Hope: Wisdom and Resilience from the Edge of Climate Change. Academic articles on Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks include:

- Murray, G. and Burrows, D. (2017) ‘Understanding Power in Indigenous Protected Areas: the Case of the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks’, Human Ecology. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-017-9948-8

- Murray, G. and King, L. (2012) ‘First Nations Values in Protected Area Governance: Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks and Pacific Rim National Park Reserve’, Human Ecology, 40(3), pp. 385–395. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10745-012-9495-2

- Robinson, L. W. et al. (2012) ‘“We Want Our Children to Grow Up to See These Animals:” Values and Protected Areas Governance in Canada, Ghana and Tanzania’, Human Ecology, 40, pp. 571–581. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-012-9502-7

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks also provides the setting for land-based learning and engagement with Nuu-chah-nulth language and culture.

- The Raincoast Education Society, formed in 2000, offers a variety of immersive land-based learning, cultural programs, and language education for youth and adults in and around Clayoquot and Barkley Sounds. RES also conducts research and monitoring, all in support of community-based stewardship. See their website at https://raincoasteducation.org/

- The West Coast N.E.S.T. is a collective of organizations, cultures, and communities convened through the Clayoquot Biosphere Trust and includes Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. The N.E.S.T helps people find courses and transformative learning experiences with community organizations, businesses, and individuals in the region. See their website at https://www.westcoastnest.org/

Relationship to the Business Community

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks have never been about excluding non-Indigenous peoples from Tla-o-qui-aht territory. Rather, as an alternative to the BC Treaty Process and comprehensive land claims, they are about finding alternative pathways to economic certainty that uphold Tla-o-qui-aht laws, rights, and responsibilities to the territory.

Growing from their outreach with area businesses, Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks have established the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks Allies program. Participating businesses contribute financially to the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks (see section on Moose #2: Financial Solutions). In addition, these businesses pledge to uphold Tla-o-qui-aht jurisdiction, operate consistent with the Tribal Parks Land Vision, report concerns such as poaching and dumping to Tribal Parks Staff, and educate themselves, their staff, and guests about local history, politics, reconciliation, and the Allies program. In return, participating businesses can use the Tribal Parks Allies logo in their marketing, and they are profiled on the Tribal Parks Allies website. Local non-profit organizations, charities, and individual donors can also be recognized as Allies.

Years of relationship-building with the business community and others in Tofino have paid off, and former Tofino Mayor Josie Osborne is a staunch supporter of Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. When Imperial Metals indicated an interest in proceeding with test drilling at the proposed Fandora mine site in Tranquil Tribal Park, both the town and Tofino and the city of Victoria voted in support of the Tla-o-qui-aht mining moratorium despite exploration permits issued by the British Columbia government (Vice, June 11, 2014).

The Canoe Creek and Haa-ak-suuk hydroelectric projects have been created in partnership with the Barkley Project Group, which has allowed Tla-o-qui-aht Nation to build both the financial and technical capacity to develop additional hydro projects in the Tribal Parks. Subsequent projects are planned to be wholly Tla-o-qui-aht-owned.

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks and the Four Moose

Moose #1: Jurisdiction

Treaties and agreements; competing legal interests in the land, e.g. forestry or mining licenses

Although the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation previously participated in the BC Treaty Process, they have since decided to leave the process, in effect pursuing Tribal Parks as an alternative pathway to achieving reconciliation, self-determination, and economic certainty on their territories.

The Ha’uukmin Tribal Park management plan, and the Tribal Parks more generally, have been used in consultation processes to evaluate various proposed activities in the Tribal Parks, such as a jet-ski enterprise and old-growth cutting permits. Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks have not relied on fighting existing permits and licenses such as those permitting old-growth logging. Rather, the Tribal Parks’ strategy is to establish a system of counter-governance for the area that will eventually render these government-issued permits and licenses obsolete and inoperable. After all, these permits have never been legitimate according to either Tla-o-qui-aht law or Canadian constitutional obligations to Indigenous Peoples.

Today, Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks coexist with numerous jurisdictions, including the municipality of Tofino, private property, forestry tenures on provincial land, provincial parks, and Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. The Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere Reserve also overlaps with the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks.

Moose #2: Financial Solutions

Although the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation previously participated in the BC Treaty Process, they have since decided to leave the process, in effect pursuing Tribal Parks as an alternative pathway to achieving reconciliation, self-determination, and economic certainty on their territories.

The Ha’uukmin Tribal Park management plan, and the Tribal Parks more generally, have been used in consultation processes to evaluate various proposed activities in the Tribal Parks, such as a jet-ski enterprise and old-growth cutting permits. Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks have not relied on fighting existing permits and licenses such as those permitting old-growth logging. Rather, the Tribal Parks’ strategy is to establish a system of counter-governance for the area that will eventually render these government-issued permits and licenses obsolete and inoperable. After all, these permits have never been legitimate according to either Tla-o-qui-aht law or Canadian constitutional obligations to Indigenous Peoples.

Today, Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks coexist with numerous jurisdictions, including the municipality of Tofino, private property, forestry tenures on provincial land, provincial parks, and Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. The Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere Reserve also overlaps with the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks.

Moose #3: Capacity building

Capacity building in Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks focuses on language and culture revitalization and the Tribal Parks Guardians program.

Moose #4: Cultural Keystone Species and Places

Protection and response to threats

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks protect species and places of special significance to Tla-o-qui-aht subsistence, identity, and culture.

Challenges, Lessons Learned, and Encouragement for IPCA Nations and Allies

Relationships with non-Indigenous conservation organizations, businesses, the town of Tofino, and Parks Canada have played important roles in the success of Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. However, these relationships took time to build. When the blockades on Meares Island took place in 1984, Tofino was a primary resource town dependent on an industrial logging and fishing economy.

Today, tourism is the main economic driver. Large-scale tourism also poses a challenge for Tla-o-qui-aht territory. Although the largest town, Tofino, only has a year-round population of about 2,200, more than 1 million tourists visit every year. Sewage outflows from the town have contaminated clam beds traditionally harvested by the Tla-o-qui-aht people. Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks continue to advocate for a sewage treatment plant for Tofino, while Tribal Parks Guardians are removing marine debris and pollution to restore these traditional food sources to their prior health and abundance.

Along logging roads in the Ha-uukmin Tribal Park, large numbers of random campers have caused environmental damage and left piles of garbage (Alberni Valley News, Sept. 1, 2020). Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks is considering gating the road in order to better manage access. Tribal Parks Guardians have also conducted patrols and hauled out garbage.

Online Videos

- National Observer video about Tribal Parks

- For our Grandchildren

- Clayoquot Tribal Parks and First Nations Old-Growth Protection

- A Visit to Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks: Joe’s Studio in the Forest

- Canoe Creek Hydro and Tla-O-Qui-Aht First Nations

- Meares35 Celebration in Victoria, BC. April 2019

- Meares35 Chief Moses Martin Reflects on Tribal Parks

- Meares35 Anniversary of the Peaceful Blockade, April 21, 2019

- Feature documentary of Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve, including Tribal Parks

Additional Resources

Introduction to Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks

- Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks Brochure (2013)

- National Observer feature on Tla-o-qui-aht feature on Tribal Parks

- National Geographic magazine feature about Tribal Parks

- May 1985 article in New York Times

- Article about how Tribal Parks have been articulating an alternative vision, from the logging blockades on Meares Island to the Tranquil Tribal Park in opposition to the proposed Fandora Mine (Vice, June 11, 2014)

Language and Tribal Parks

Tribal Parks Allies

Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks hydro projects

Tribal Parks and COVID-19

Academic Articles

- Murray, G. and Burrows, D. (2017) ‘Understanding Power in Indigenous Protected Areas: the Case of the Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks’, Human Ecology.

- Murray, G. and King, L. (2012) ‘First Nations Values in Protected Area Governance: Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks and Pacific Rim National Park Reserve’, Human Ecology, 40(3), pp. 385–395.

- Robinson, L. W. et al. (2012) ‘“We Want Our Children to Grow Up to See These Animals:” Values and Protected Areas Governance in Canada, Ghana and Tanzania’, Human Ecology, 40, pp. 571–581.